Room 28 Blog. Hannelore Brenner

"So much Love and Tenderness". Obituary for Evelina Merová

Evelina Merová, née Landová, one of the surviving "Girls of Room 28" passed away in Prague on 8 February 2024. As I write these lines, on 13 February around 2 pm, she is being laid to rest in the Jewish Cemetery in Prague. My thoughts are with her and her beloved family.

I was very sad when Evelina's son Viktor Naimark broke the news to me on the morning of 8 February. I know how much Viktor loves his mother, I always felt it when I saw them together or when she spoke of him - or he of her. A kind of secret, a loving intimacy connected mother and son, and I know that this is also true for Evelina and her daughter Irene, who lives in St. Petersburg. An understanding without words. There was gentleness and forbearance in their dealings with each other.

The "secret" is echoed in Viktor's words, which can be found in his epilogue to his mother's autobiography "Lebenslauf auf einer Seite" (Vita on one Page): "Now that I am an adult, I admire more and more that my mother was able to give us so much love and tenderness despite all the atrocities and horrors she survived."

A Heart made of Auschwitz Earth

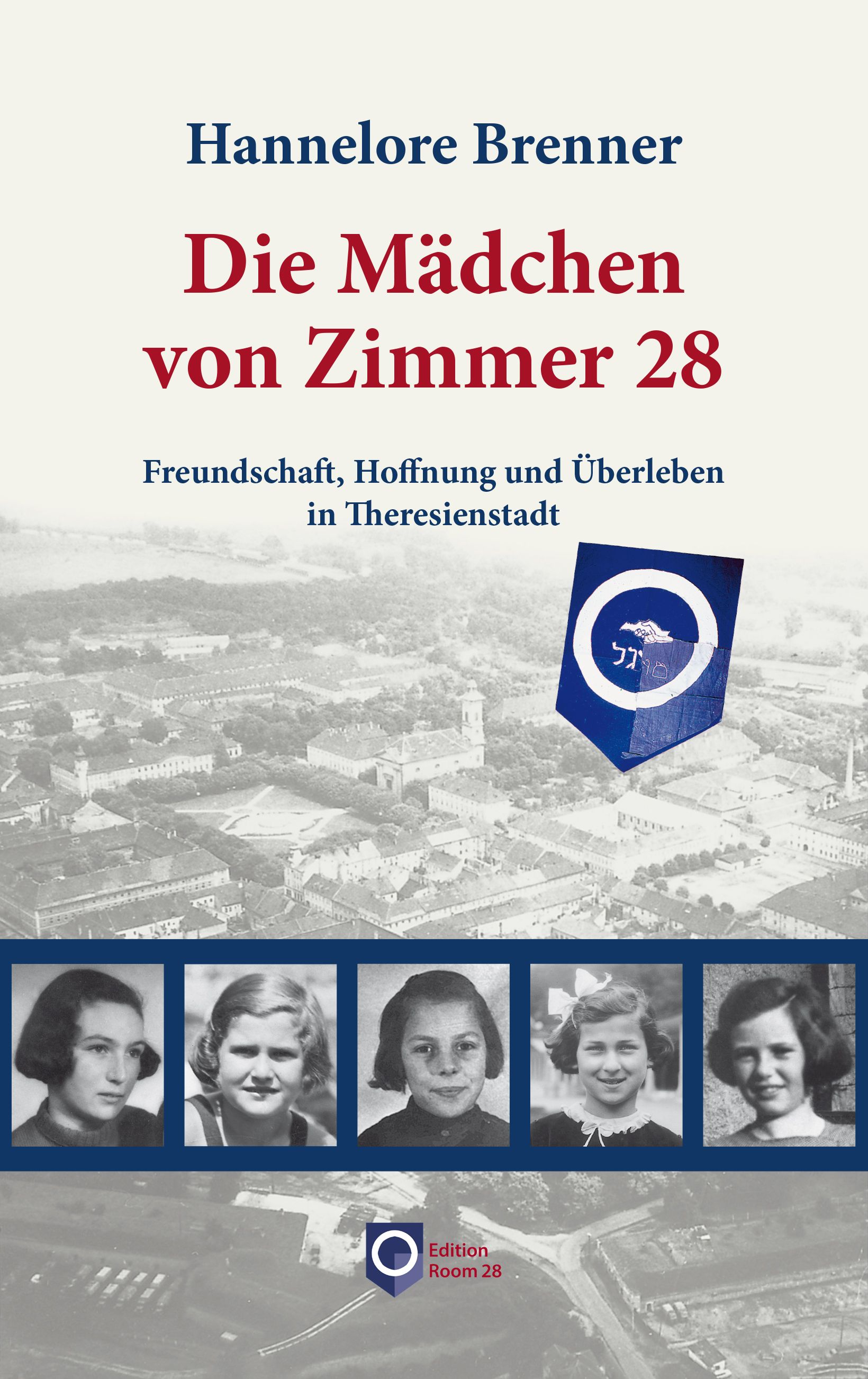

"Despite all the atrocities and horrors she survived". It was terrible enough what Evelina Landová, born on 25 December 1930 in Prague, had to experience after Nazi-Germany occupied her beloved homeland on 15 March 1939 and Jews were gradually deprived of their human rights and ultimately deported. On 28 June 1942, the Landa family was transported to the Theresienstadt ghetto. Until December 1943, she lived in the Girls' Home L 410, in Room 28. She was 11 to 12-years-old and still experienced life in Room 28 as a kind of shelter, which she would associate decades later also with good memories. But the transport on 15 December 1943 marked the beginning of an odyssey through hell. She spent her 13th birthday in the children's block run by Fredy Hirsch in the Theresienstadt family camp in Auschwitz-Birkenau. I will never forget how she told me about her friend Harry and his 13th birthday: "I modelled a little heart for him out of Auschwitz earth and wrote inside: "From Eva to Harry’s birthday. 6 March 1944.

"On 7 March 1944, she received the shocking news of Fredy Hirsch's death - he was an idol to her, as he was to many children in Terezín. On 8/9 March 1944, almost all people from the Theresienstadt September transport, more than 4,000 people, were murdered in the gas chambers, among them four girls who had lived with Evelina in Room 28 in the Girls Home in the Theresienstadt ghetto: Pavla Seiner, Olile Löwy, Zdenka Löwy and Ruth Popper. Her father Emil Landa died on 13 April in Auschwitz-Birkenau. Evelina's mother Ilse survived the selection with her in July 1944 and they were sent to Stutthof concentration camp, then to a labor camp in Guttau, where her mother died. "I think it was the lowest point of my life. And yet I can't say what I felt or thought. We were living under absolutely dreadful conditions, in a state of emergency, in a state of shock...

Half a Century later

It was the beginning of 2005 in Berlin-Kreuzberg. The exhibition

The Girls of Room 28, which was shown for the first time in Schwerin on 23 September 2004, was shown at Reinhardswald Primary School. Evelina was a guest. She answered questions from children aged between 10 and 11. Questions and answers ran like a quick game of ping-pong. The children took increasing interest in asking her more and more questions, and Evelina always answered briefly and concisely, factually, sometimes only with a definite Yes or No. "Was it bad for you when your mum died?" asked one girl. "Yes," said Evelina and smiled, as I so often saw her do when a question met the unspeakable.

Between 2014 and 2015, I worked intensively with Evelina on her autobiographical memoirs, which I published in March 2016 in Edition Room 28 under the title Lebenslauf auf einer Seite. Prague - Theresienstadt - Auschwitz-Birkenau - Leningrad. In her manuscript, I discovered breaks, gaps, passages that referred to experiences that must have been terrible for her, but which she described with little empathy for herself. I asked questions, again and again, carefully, cautiously. It seemed to me that some of her experiences were covered by a protective layer of ice. I wanted to break through it, to create something like an excitement, a vibration of her soul, to 'breathe' it into the text and model it a little, just as Evelina modelled the heart out of Auschwitz earth for her friend Harry.

During this work in 2015-2016, I felt closer to Evelina than ever before. I learnt things I hadn't known about before, even though I had many conversations with her and her friends from 1998 onwards for the book The Girls of Room 28. I knew one thing for sure: when it came to facts, to objective reports about events she knew about, I could rely on her. She endeavored to be factual, clear, as comprehensible and logical as possible - "logical" or "unlogical" were one of her favorite words. She kept silent if she did not know something. But now I learnt that and how she could remain silent, even and especially when she knew something very well.

More and more I realized that Evelina had developed very subtle mechanisms to avoid the Unspeakable, not only for her own sake but also for the sake of others; to be able to live with the Unspeakable. Silence was one of them. It was a deliberate silence, often combined with a hint of a smile. She had a touching, engaging, sometimes a cheeky-friendly smile - especially in moments like these. A beautiful smile. It often became very quiet. And the question remained: what was going on inside her? What images flashed across her mind and soul?

Poetry shall be...

As a little girl, Evelina, like many other children, kept a poetry album. She never forgot her grandfather's lines:

Poetry shall be what is written in this little book. Poetry shall be everything that happens in your life. "My grandfather's wish

was wonderful," she writes in the introduction to her memoirs. "Unfortunately - his wish did not come true. What happened in my life was not poetry...."

And yet, the longing for poetry must have remained strong in her, despite all the atrocities and horrors. So strong that this longing was passed on to her children. How else can it be explained that Viktor Naimark, who moved from St. Petersburg to Frankfurt on the Main in 2000, creates an art full of poetry? No naive poetry. A disturbing poetry. Poetry that knows about the atrocities and horrors and yet is filled with light and love.

In 2022, at Viktor's initiative, our association

Room 28 made a contribution to the

Festjahr 2021 – 1700 jüdisches Leben in Deutschland (Anniversary year 2021 - 1700 years of Jewish life in Germany) with the project

“Jewish Identity in the Context of European Cultural History”. Part of the project was an exhibition created by Viktor and shown in Karlsruhe in March 2022 titled

Das Damals im Heute (The Past in the Presence). Jürgen Walter, Professor of Media Technology at the University of Karlsruhe, saw the exhibition, read Evelina's autobiography and discovered Viktor's epilogue. He then produced a small, haunting film. Whenever I watch this film, I have the feeling that Viktor's artwork together with his epilogue to his mother's autobiography beautifully conveys what was unspeakable for Evelina.

In silent memory of Evelina and in compassionate thoughts of Evelina's children and grandchildren, Hannelore

Blog von Hannelore Brenner